Eastside Heritage Center has a collection of 120 oversize textiles, which includes handmade quilts, institutional banners and flags, and other oversize home textiles. This collection has been stored at our off-site storage facility in archival boxes for many years. Folding textiles and storing them in boxes is not an ideal long term storage option. Current industry best practices recommend storing flat textiles rolled onto archival tubes with a tissue paper barrier, when they cannot be stored flat.

To ensure the long-term safety of the collection, EHC decided to rehouse the textiles. We applied for two grants through 4 Culture to build a rolled textile rack and were awarded funds!

First, our collections staff disassembled and removed the existing shelving unit and prepared the space for installation. We used a low-cost racking option that uses materials you can find at the local hardware store. (Links to the resources we used are at the end of this article) Two terrific volunteers, Steve and Tim, helped install the racking at our storage facility. With the racking prepared, we were able to move on to the rehousing of the quilt collection.

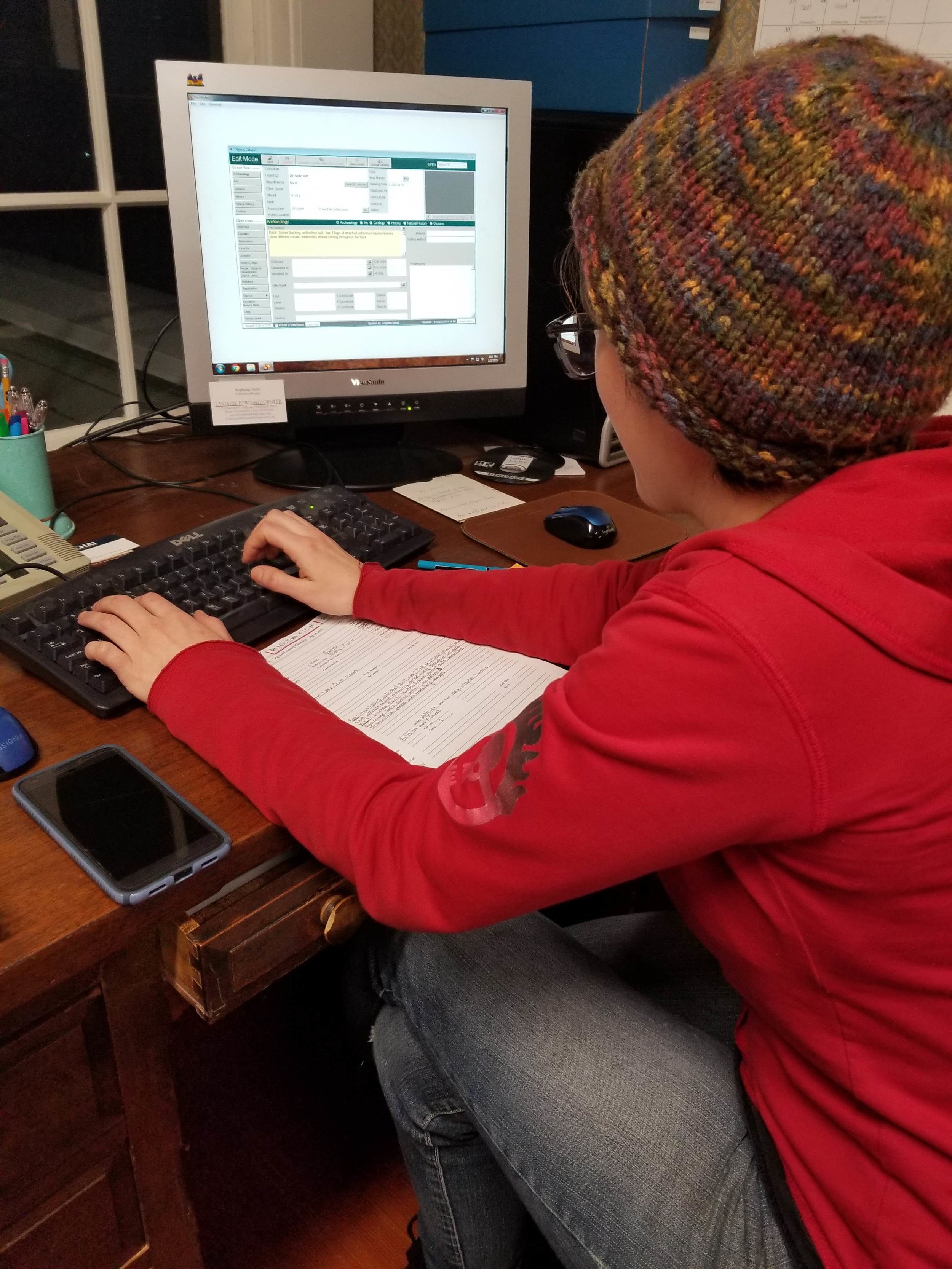

Last fall we hired two interns to help with this project. Under their care, each textile was unfolded, vacuumed and cleaned as necessary, photographed, and its record was updated in our database. Then it was rolled around an archival tube, using methods recommended by the Foundation of the American Institute for Conservation. Once the textiles were rolled and stored on the racks they were tagged with an identification tag. So far, the interns have processed over 50 textiles.

Suspending the tubes on racking will prevent damage to the textile fibers that can be caused by folding and stacking in boxes. By installing a wall mounted racking system, collections storage space and shelving units will be freed up for storage of other collections items. Each wrapped roll will be tagged with a hanging photo id tag, which will help prevent unnecessary handling. It will be easier for collections staff to monitor the condition of the textiles, identify items for exhibit or research, and safely remove them from storage without having to handle other items in a box or repeatedly fold and unfold a textile.

This, like most collections work, is ongoing. We have successfully filled the existing racking and are making plans for more. Grant funds and private donations are the main way we are able to undertake projects like this one.

This project was funded by 4 Culture.