No. 4 | March 20, 2019

Eastside Stories

Eastside Stories is our way of sharing Eastside history through the many events, people places and interesting bits of information that we collect at the Eastside Heritage Center. We hope you enjoy these stories and share them with friends and family.

The Points Communities

A visitor to the Eastside, headed across the SR-520 bridge toward Kirkland, Redmond or Bellevue will first cross through four small cities: Medina, Hunts Point, Yarrow Point and Clyde Hill. While the large Eastside cities have populations numbering in the high ten-thousands to well over 100,000, the Points Communities cities range from just 420 souls in Hunts Point to 3,200 in Medina.

Just where did these little burgs come from? And do they really make sense in our modern patterns of governance?

The Points Communities were settled around the same time as the rest of the Eastside, and since the easiest transport was by water, their proximity to Seattle allowed them to turn into significant communities early on. The Lake Washington Reflector newspaper gave Medina and Bellevue equal billing on the masthead into the 1930s.

As Seattle grew, and ferry service became reliable, the points offered both affordable commuting homes and waterfront mansions for the wealthy. The three points themselves—Evergreen, Hunts, Yarrow—had a large number of vacation homes in the early years, as the upper middle class of Seattle could enjoy waterfront living for the summer while staying within commuting distance of Seattle. The uplands of Medina attracted more year-round commuters, while Clyde Hill and the uplands of Yarrow Point were largely agricultural.

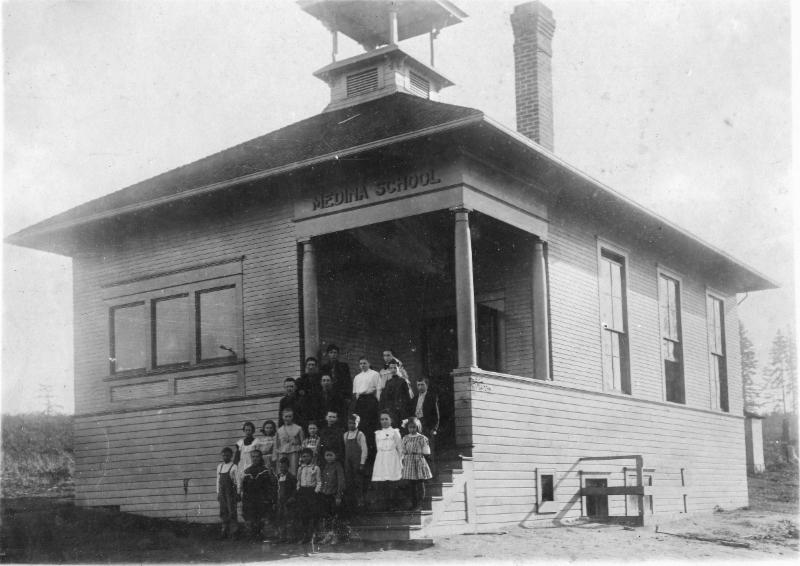

Medina School opened in 1909. At that time, most older children from Medina took the ferry to Garfield High School in Seattle.

These communities grew slowly until major change came to the Eastside with the opening of the Mercer Island floating bridge and the post-war housing boom. Kirkland had long been the commercial center of the Eastside, but Bellevue gradually expanded its commercial role and by the 1950s was getting quite built up. Unlike other established Eastside towns—Renton, Issaquah, Kirkland, Redmond, Bothell—Bellevue had never incorporated as a city. It took care of that omission in 1953, creating a new city centered in what is now the downtown area.

Clyde Hill incorporated the same year as Bellevue, but there was little consensus within the rest of the points about their future. The points area was now cut off from the rest of unincorporated King County by Bellevue, Clyde Hill and Houghton (a separate city that merged with Kirkland in 1968). With the prospects of higher density growth and a new floating bridge, residents wanted to control their own planning and zoning.

City government for the points seemed inevitable, but what would that look like? Annexation to Bellevue was certainly an option, and the prevailing “good government” view at the time was that small cities were inefficient and unnecessary. The Bellevue American newspaper and the King County Municipal League argued for annexation to Bellevue, and many points residents agreed.

Bay School, located where Hunts Point City Hall stands today, served the points and north Clyde Hill. Older children from Bay School attended Kirkland High School.

But, at the same time, each community had its faction that favored incorporation. The points area had long been divided by school district and community club boundaries, and the incorporation movements followed these boundaries, with the Medina Community Club joining forces with the Evergreen Point club.

Pro-annexation residents of Medina applied to join Bellevue, but annexations take time, and the incorporation forces in Medina got on the ballot before the annexation process could be completed. If Medina incorporated, annexation to Bellevue would be impossible for the other points, so in 1955 incorporation measures went on the ballot on the same date in Medina, Hunts Point and Yarrow Point. Medina and Hunts Point voters approved their measures, and it took another four years to get a successful vote in Yarrow Point.

Sunnyside Landing provided one of the ferry connections for Yarrow Point. It stood at what is today a public beach access at the foot of NE 42nd Street on Cozy Cove. Ferries serving the points landed at Madison Park in Seattle, allowing commuters to take a streetcar directly to downtown Seattle. (Photo courtesy of Washington State Archives)

It turns out that small cities are not such a bad idea, especially if they have robust tax bases. In the 1950s it became very common across the country for suburban cities to contract for complex services while keeping control of politically important functions like planning. The Points Communities all contract with Bellevue for fire service and Bellevue operates the water and sewer utilities.

Medina provides police protection to Hunts Point and Clyde Hill provides police service to Yarrow Point. All four communities make extensive use of private firms for planning and other technical work.

So there they sit, four fiercely independent cities that certainly appreciate the amenities of the big cities next door, but have no interest in joining them.

Learn more about the Eastside and the Point Communities. Books available from Eastside Heritage Center include:

A Point in Time (Yarrow Point) is out of print but available at the King County Library

Our Mission To steward Eastside history by actively collecting, preserving, and interpreting documents and artifacts, and by promoting public involvement in and appreciation of this heritage through educational programming and community outreach.

Our Vision To be the leading organization that enhances community identity through the preservation and stewardship of the Eastside’s history.

Eastside Heritage Center is supported by 4 Culture