While the remaining charges were still pending against all the defendants, the local media kept the affair in the public spotlight. Beginning in January 1923 the Seattle Star published a series entitled “The Ferry Deal.” It began with six brief pieces by W.E. Chambers, a former King County commissioner, who explained how the county had gotten into the ferry business and its entanglements with John Anderson. In mid-March, “in line with [its] policy to publish both sides of any controversy,” the Star had Thomas Daugherty offer his own six-part interpretation of events.

Two weeks before his own trial at the end of March 1923, John Anderson was called before the county commissioners to explain how in one year he was able to take the ferry system he had run as a county employee and, as the private lessee, turn 1921’s $234,000 deficit into 1922’s $40,000 profit and decrease disbursements by 200%. He explained quite simply that he could run the system now as a business—cut salaries, employees, unfavorable routes-- free from the constraints he had had as a public official, when “politics interfered.” (Left unmentioned was the fact as Superintendent of Transportation he had front-loaded the huge expenditures for new facilities and refurbished vessels before the commissioners turned the system over to him.)

The rest of the story ended abruptly. When the Anderson group went to trial at month’s end, the judge, after hearing all the county’s evidence and without waiting for the defense to present its case, issued a directed verdict in favor of the defendants and chided the prosecutor for having brought the indictments on the weak evidence he had. That ended the matter for the commissioners as well.

The lake ferries were now all being operated privately, although the county owned the boats leased to Anderson. In 1924 Anderson’s Lake Washington Ferries advertised daily excursions on the county’s steamer ‘Atlanta’ between Lake Washington and the Seattle waterfront through the Ship Canal and locks. Lake cruises and excursions were more lucrative than the ferry routes. In 1925 Anderson announced that he would turn boats back on the following January 1 (which the lease allowed him to do) unless the county would pay $70,000 to buy and install a new engine on the ‘Lincoln. ’ Or the county could just give him the boat and he would pay for the engine. As one wag suggested in the newspaper, maybe Anderson could compromise with an Evinrude outboard.

Anderson persevered; in 1927 his lease was extended without fanfare until 1951. But it was becoming clear that the real culprit in the “unprofitability” of ferry service was the automobile. Paving of the highway encircling the lake was completed in 1923, and the East Channel bridge to Mercer Island’s east shore opened in that year. A floating bridge between the island and Seattle had been proposed in 1921, but it wasn’t seriously considered until 1930. After funds became available through the Public Works Administration and serious planning began, one final major showdown over the ferry lease developed.

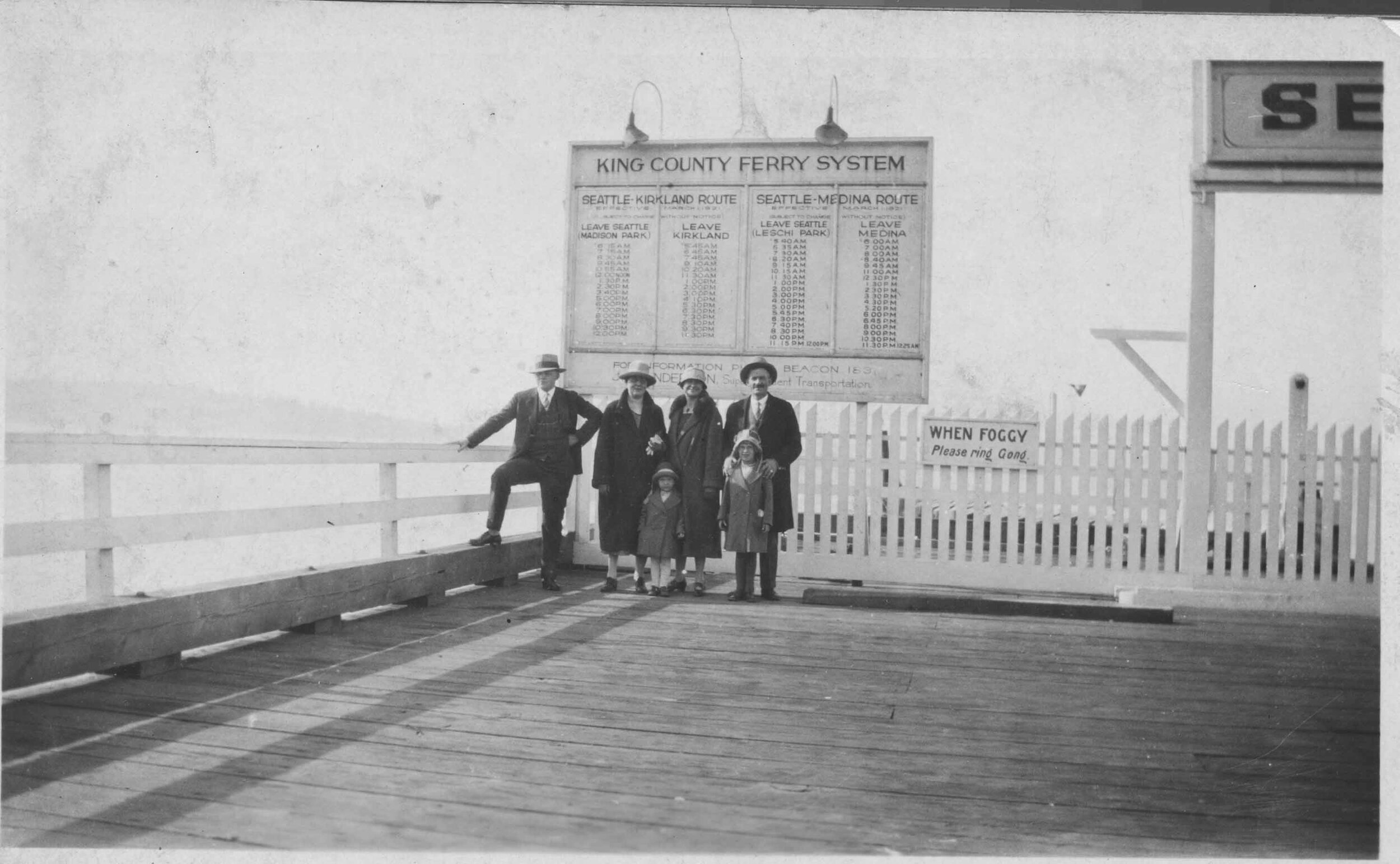

The Washington Toll Bridge Authority feared it would be difficult to pay off the bonds, which had financed the bridge, with bridge tolls so long as competition in the form of lake ferries continued. Under this pressure, in December 1938 the county commissioners cancelled Anderson’s lease. He fought back by filing a claim for anticipated damages. Negotiations among the three parties finally led to a settlement. The county would not cancel the lease, and the Toll Authority would pay Anderson $35,000. In exchange, he would terminate the Leschi-Medina route and the runs to Mercer Island once the bridge opened. The run between Madison Park and Kirkland would continue to operate.

There was one final unpleasant chapter to play out. The floating bridge opened on July 2, 1940 and that month Anderson announced that he was returning the ferry ‘Washington’ and the docks at Medina and Roanoke to the county and planned to return the launch ‘Mercer’ the following month. When the boats were returned they were found to be in very poor condition. One had had its federal license cancelled because of unseaworthiness. The commissioners ruled that Anderson would have to pay a sum, as yet undetermined, in lieu of repairing the vessels. Anderson countered that the boats were “just wore out” and that if they had been owned by a private business, they would have been “depreciated off the books long ago.” The lease, however, provided that he was to return all boats leased in good condition. Appraisers from each side were unable to agree on the present value of the boats; the county’s property agent was left to salvage what he could from the two boats.

John Anderson died of a heart attack on May 18, 1941. His widow, Emilie, and his longtime right-hand man, Harrie Tompkins, continued to operate the Kirkland ferry under the lease with the county. During World War II the ferry ‘Lincoln’ ferried shipyard workers between Madison Park and the Lake Washington Shipyard at Houghton. The ‘Leschi’ continued to make the Kirkland-Madison Park run.

In July 1947 Emilie Anderson wrote the county commissioners announcing that Lake Washington Ferries would not continue its lease beyond the end of the year and might suspend ferry service before then. But the enterprise just kept staying afloat. On January 30, 1950, however, the Seattle Times ran three photos of teary longtime passengers and onlookers—including faithful Harrie Tompkins--saying goodbye to the ‘Leschi’ on what was expected to be its final run. But no, there was still more. Members of the union operating the boat attempted to continue to operate it so long as revenues could meet wages. Their effort could not be sustained, however. On August 31, 1950 the Leschi made its truly final run on the lake, and vehicle ferry service between the Eastside and Seattle ended. In November the county commissioners voted to offer to the cities of Kirkland and Seattle the piers and land adjacent to them at their old ferry landings, for use as public parks. And so this colorful and complicated piece of local history finally came to an end.